Aurelius, Marcus

| Marcus Aurelius |

| Emperor of the Roman Empire |

|

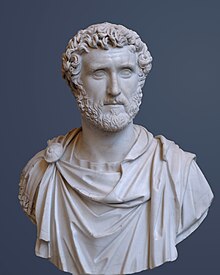

| Bust of Marcus Aurelius in the Glyptothek, Munich |

| Reign |

8 March 161–169

(with Lucius Verus);

169–177 (alone);

177–March 180

(with Commodus)

(&000000000000001900000019 years, &00000000000000090000009 days) |

| Full name |

Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus |

| Born |

26 April 121(121-04-26) |

| Birthplace |

Rome |

| Died |

17 March 180(180-03-17) (aged 58) |

| Place of death |

Vindobona or Sirmium |

| Buried |

Hadrian's Mausoleum |

| Predecessor |

Antoninus Pius |

| Successor |

Commodus (alone) |

| Consort to |

Faustina the Younger |

| Dynasty |

Antonine |

| Father |

Marcus Annius Verus |

| Mother |

Domitia Lucilla |

| Children |

13, incl. Commodus, Marcus Annius Verus, Antoninus and Lucilla |

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus[notes 1] (26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman Emperor from 161 to 180. He ruled with Lucius Verus as co-emperor from 161 until Verus' death in 169. He was the last of the "Five Good Emperors", and is also considered one of the most important Stoic philosophers. During his reign, the empire defeated a revitalized Parthian Empire; Aurelius' general Avidius Cassius sacked the capital Ctesiphon in 164. Aurelius fought the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatians with success during the Marcomannic Wars, but the threat of the Germanic Tribes began to represent a troubling reality for the empire. A revolt in the east led by Avidius Cassius failed to gain momentum and was suppressed immediately.

Marcus Aurelius' work Meditations, written in Greek while on campaign between 170 and 180, is still revered as a literary monument to a government of service and duty. It serves as an example of how Aurelius approached the Platonic ideal of a philosopher-king and how he symbolized much of what was best about Roman civilization.[3]

[edit] Sources

The major sources for the life and rule of Marcus Aurelius are patchy and frequently unreliable. The most important group of sources, the biographies contained in the Historia Augusta, claim to be written by a group of authors at the turn of the fourth century, but are in fact written by a single author (referred to here as "the biographer") from the later fourth century (c. 395). The later biographies and the biographies of subordinate emperors and usurpers are a tissue of lies and fiction, but the earlier biographies, derived primarily from now-lost earlier sources (Marius Maximus or Ignotus), are much better.[4] For Marcus' life and rule, the biographies of Hadrian, Pius, Marcus and Lucius Verus are largely reliable, but those of Aelius Verus and Avidius Cassius are full of fiction.[5]

Tutor Fronto and various Antonine officials survives in a series of patchy manuscripts, covering the period from c. 138 to 166.[6] Marcus' own Meditations offer a window on his inner life, but are largely undateable, and make few specific references to worldly affairs.[7] The main narrative source for the period is Cassius Dio, a Greek senator from Bithynian Nicaea who wrote a history of Rome from its founding to 229 in eighty books. Dio is vital for the military history of the period, but his senatorial prejudices and strong opposition to imperial expansion obscure his perspective.[8] Some other literary sources provide specific detail: the writings of the physician Galen on the habits of the Antonine elite, the orations of Aelius Aristides on the temper of the times, and the constitutions preserved in the Digest and Codex Justinianus on Marcus' legal work.[9] Inscriptions and coin finds supplement the literary sources.[10]

[edit] Early life and career

Main article: Early life and career of Marcus Aurelius

[edit] Family, childhood, and early education, 121–36

Marcus' family originated in Ucubi (now called Espejo), a small town southeast of Córdoba in Iberian Baetica. The family rose to prominence in the late first century AD. Marcus' great-grandfather Marcus Annius Verus (I) was a senator and (according to the Historia Augusta) ex-praetor; in 73–74 his grandfather Marcus Annius Verus (II) was made a patrician.[11][notes 2] Verus' elder son—Marcus Aurelius' father—Marcus Annius Verus (III) married Domitia Lucilla.[14] Lucilla was the daughter of the patrician P. Calvisius Tullus Ruso and the elder Domitia Lucilla. The elder Domitia Lucilla had inherited a great fortune (described at length in one of Pliny's letters) from her maternal grandfather and her paternal grandfather by adoption.[15] The younger Lucilla would acquire much of her mother's wealth, including a large brickworks on the outskirts of Rome—a profitable enterprise in an era when the city was experiencing a construction boom.[16]

Bust of Marcus Aurelius as a young boy (Capitoline Museum). Anthony Birley, Marcus' modern biographer, writes of the bust: "This is certainly a grave young man."

[17]

Lucilla and Verus (III) had two children: a son, Marcus, born on 26 April 121, and a daughter, Annia Cornificia Faustina, probably born in 122 or 123.[18] Verus (III) probably died in 124, during his praetorship, when Marcus was only three years old.[19][notes 3] Though he can hardly have known him, Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations that he had learned "modesty and manliness" from his memories of his father and from the man's posthumous reputation.[21] Lucilla did not remarry.[19] Lucilla, following prevailing aristocratic customs, probably did not spend much time with her son. Marcus was in the care of "nurses".[22] Marcus credits his mother with teaching him "religious piety, simplicity in diet" and how to avoid "the ways of the rich".[23] In his letters, Marcus makes frequent and affectionate reference to her; he was grateful that, "although she was fated to die young, yet she spent her last years with me".[24]

After his father's death, Aurelius was adopted by his paternal grandfather Marcus Annius Verus (II).[25] Another man, Lucius Catilius Severus, also participated in his upbringing. Severus is described as Marcus' "maternal great-grandfather"; he is probably the stepfather of the elder Lucilla.[25] Marcus was raised in his parents' home on the Caelian Hill, a district he would affectionately refer to as "my Caelian".[26] It was an upscale region, with few public buildings but many aristocratic villas. Marcus' grandfather owned his own palace beside the Lateran, where Marcus would spend much of his childhood.[27] Marcus thanks his grandfather for teaching him "good character and avoidance of bad temper".[28] He was less fond of the mistress his grandfather took and lived with after the death of Rupilia Faustina, his wife.[29] Marcus was grateful that he did not have to live with her longer than he did.[30]

Marcus was taught at home, in line with contemporary aristocratic trends;[31] Marcus thanks Catilius Severus for encouraging him to avoid public schools.[32] One of his teachers, Diognetus, a painting-master, proved particularly influential; he seems to have introduced Marcus to the philosophic way of life.[33] In April 132, at the behest of Diognetus, Marcus took up the dress and habits of the philosopher: he studied while wearing a rough Greek cloak, and would sleep on the ground until his mother convinced him to sleep on a bed.[34] A new set of tutors—Alexander of Cotiaeum, Trosius Aper, and Tuticius Proculus[notes 4]—took over Marcus' education in about 132 or 133.[36] Little is known of the latter two (both teachers of Latin), but Alexander was a major littérateur, the leading Homeric scholar of his day.[37] Marcus thanks Alexander for his training in literary styling.[38] Alexander's influence—an emphasis on matter over style, on careful wording, with the occasional Homeric quotation—has been detected in Marcus' Meditations.[39]

[edit] The Pompey connection

According to the notoriously unreliable Historia Augusta, he is the great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandson of Pompey the Great through his daughter Pompeia Magna. His paternal grandmother Rupilia was the great granddaughter of Scribonia (daughter of Lucius Scribonius Libo consul 16) , who was herself the great granddaughter of Pompey the Great on both her parents side. This would make Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus the only emperors directly related to the son-in-law and rival of Julius Caesar.

[edit] Civic duties and family connections, 127–36

Bust of Hadrian (National Archaeological Museum of Athens). The Emperor Hadrian patronized the young Marcus, and may have planned to make him his long-term successor.

[40]

In 127, at the age of six, Marcus was enrolled in the equestrian order on the recommendation of Emperor Hadrian. Though this was not completely unprecedented, and other children are known to have joined the order, Marcus was still unusually young. In 128, Marcus was enrolled in the priestly college of the Salii. Since the standard qualifications for the college were not met—Marcus did not have two living parents—they must have been waived by Hadrian, Marcus' nominator, as a special favor to the child.[41] Hadrian had a strong affection for the child, and nicknamed him Verissimus, "most true".[42][notes 5] Marcus took his religious duties seriously. He rose through the offices of the priesthood, becoming in turn the leader of the dance, the vates (prophet), and the master of the order.[44]

Hadrian did not see much of Marcus in his childhood. He spent most of his time outside Rome, on the frontier, or dealing with administrative and local affairs in the provinces.[notes 6] By 135, however, he had returned to Italy for good. He had grown close to Lucius Ceionius Commodus, husband of the daughter of Gaius Avidius Nigrinus, a dear friend of Trajan who was executed for attempting to overthrow Hadrian early in his reign. In 136, shortly after Marcus assumed the toga virilis symbolizing his passage into manhood, Hadrian arranged for his engagement to one of Commodus' daughters, Ceionia Fabia.[46] Marcus was made prefect of the city during the feriae Latinae soon after (he was probably appointed by Commodus). Although the office held no real administrative significance—the full-time prefect remained in office during the festival—it remained a prestigious office for young aristocrats and members of the imperial family. Marcus conducted himself well at the job.[47]

Through Commodus, Marcus met Apollonius of Chalcedon, a Stoic philosopher. Apollonius had taught Commodus, and would be an enormous impact on Marcus, who would later study with him regularly. He is one of only three people Marcus thanks the gods for having met.[48] At about this time, Marcus' younger sister, Annia Cornificia, married Ummidius Quadratus, her first cousin. Domitia Lucilla asked Marcus to give part of his father's inheritance to his sister. He agreed to give her all of it, content as he was with his grandfather's estate.[49]

[edit] Succession to Hadrian, 136–38

In late 136, Hadrian almost died from a haemorrhage. Convalescent in his villa at Tivoli, he selected Lucius Ceionius Commodus as his successor, and adopted him as his son.[50] The selection was done invitis omnibus, "against the wishes of everyone";[51] its rationale is still unclear.[52] After a brief stationing on the Danube frontier, Lucius returned to Rome to make an address to the senate on the first day of 138. The night before the speech, however, he grew ill, and died of a haemorrhage later in the day.[53][notes 7] On 24 January 138, Hadrian selected Aurelius Antoninus as his new successor.[55] After a few days' consideration, Antoninus accepted. He was adopted on 25 February. As part of Hadrian's terms, Antoninus adopted Marcus and Lucius Commodus, the son of Aelius. Marcus became M. Aelius Aurelius Verus; Lucius became L. Aelius Aurelius Commodus. At Hadrian's request, Antoninus' daughter Faustina was betrothed to Lucius.[56] Marcus was appalled to learn that Hadrian had adopted him. Only with reluctance did he move from his mother's house on the Caelian to Hadrian's private home.[57]

At some time in 138, Hadrian requested in the senate that Marcus be exempt from the law barring him from becoming quaestor before his twenty-fourth birthday. The senate complied, and Marcus served under Antoninus, consul for 139.[58] Marcus' adoption diverted him from the typical career path of his class. But for his adoption, he probably would have become triumvir monetalis, a highly regarded post involving token administration of the state mint; after that, he could have served as tribune with a legion, becoming the legion's nominal second-in-command. Marcus probably would have opted for travel and further education instead. As it was, Marcus was set apart from his fellow citizens. Nonetheless, his biographer attests that his character remained unaffected: "He still showed the same respect to his relations as he had when he was an ordinary citizen, and he was as thrifty and careful of his possessions as he had been when he lived in a private household."[59]

Baiae, seaside resort and site of Hadrian's last days. Marcus would holiday in the town with the imperial family in the summer of 143.

[60] (J.M.W. Turner,

The Bay of Baiae, with Apollo and Sybil, 1823)

After a series of suicide attempts, all thwarted by Antoninus, Hadrian left for Baiae, a seaside resort on the Campanian coast. His condition did not improve, and he abandoned the diet prescribed by his doctors, indulging himself in food and drink. He sent for Antoninus, who was at his side when he died on 10 July 138.[61] His remains were buried quietly at Puteoli.[62] The succession to Antoninus was peaceful and stable: Antoninus kept Hadrian's nominees in office and appeased the senate, respecting its privileges and commuting the death sentences of men charged in Hadrian's last days.[63] For his dutiful behavior, Antoninus was asked to accept the name "Pius".[64]

[edit] Heir to Antoninus Pius, 136–45

Immediately after Hadrian's death, Antoninus approached Marcus and requested that his marriage arrangements be amended: Marcus' betrothal to Ceionia Fabia would be annulled, and he would be betrothed to Faustina, Antoninus' daughter, instead. Faustina's betrothal to Ceionia's brother Lucius Commodus would also have to be annulled. Marcus consented to Antoninus' proposal.[65]

Pius bolstered Marcus' dignity: Marcus was made consul for 140, with Pius as his colleague, and was appointed as a seviri, one of the knights' six commanders, at the order's annual parade on 15 July 139. As the heir apparent, Marcus became princeps iuventutis, head of the equestrian order. He now took the name Caesar: Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar.[66] Marcus would later caution himself against taking the name too seriously: "See that you do not turn into a Caesar; do not be dipped into the purple dye—for that can happen".[67] At the senate's request, Marcus joined all the priestly colleges (pontifices, augures, quindecimviri sacris faciundis, septemviri epulonum, etc.);[68] direct evidence for membership, however, is available only for the Arval Brethren.[69]

Pius demanded that Marcus take up residence in the House of Tiberius, the imperial palace on the Palatine. Pius also made him take up the habits of his new station, the aulicum fastigium or "pomp of the court", against Marcus' objections.[68] Marcus would struggle to reconcile the life of the court with his philosophic yearnings. He told himself it was an attainable goal—"where life is possible, then it is possible to live the right life; life is possible in a palace, so it is possible to live the right life in a palace"[70]—but he found it difficult nonetheless. He would criticize himself in the Meditations for "abusing court life" in front of company.[71]

As quaestor, Marcus would have had little real administrative work to do. He would read imperial letters to the senate when Pius was absent, and would do secretarial work for the senators. His duties as consul were more significant: one of two senior representatives of the senate, he would preside over meetings and take a major role in the body's administrative functions.[72] He felt drowned in paperwork, and complained to his tutor, Fronto: "I am so out of breath from dictating nearly thirty letters".[73] He was being "fitted for ruling the state", in the words of his biographer.[74] He was required to make a speech to the assembled senators as well, making oratorical training essential for the job.[75]

On 1 January 145, Marcus was made consul a second time. He might have been unwell at this time: a letter from Fronto that might have been sent at this time urges Marcus to have plenty of sleep "so that you may come into the Senate with a good colour and read your speech with a strong voice".[76] Marcus had complained of an illness in an earlier letter: "As far as my strength is concerned, I am beginning to get it back; and there is no trace of the pain in my chest. But that ulcer [...][notes 8] I am having treatment and taking care not to do anything that interferes with it."[77] Marcus was never particularly healthy or strong. The Roman historian Cassius Dio, writing of his later years, praised him for behaving dutifully in spite of his various illnesses.[78]

A bust of Faustina the Younger, Marcus' wife (Louvre)

In April 145, Marcus married Faustina, as had been planned since 138. Since Marcus was, by adoption, Pius' son, under Roman law he was marrying his sister; Pius would have had to formally release one or the other from his paternal authority (his patria potestas) for the ceremony to take place.[79] Little is specifically known of the ceremony, but it is said to have been "noteworthy".[80] Coins were issued with the heads of the couple, and Pius, as Pontifex Maximus, would have officiated. Marcus makes no apparent reference to the marriage in his surviving letters, and only sparing references to Faustina.[81]

[edit] Fronto and further education, 136–61

After taking the toga virilis in 136, Marcus probably began his training in oratory.[82] He had three tutors in Greek, Aninus Macer, Caninius Celer, and Herodes Atticus, and one in Latin, Fronto. (Fronto and Atticus, however, probably did not become his tutors until his adoption by Antoninus in 138.) The preponderance of Greek tutors indicates the importance of the language to the aristocracy of Rome.[83] This was the age of the Second Sophistic, a renaissance in Greek letters. Although educated in Rome, in his Meditations, Marcus would write his inmost thoughts in Greek.[84] The latter two were the most esteemed orators of the day.[85]

Bust of Herodes Atticus, Marcus' tutor in Greek, from his villa at Kephissia (National Archaeological Museum of Athens)

Herodes was controversial: an enormously rich Athenian (probably the richest man in the eastern half of the empire), he was quick to anger, and resented by his fellow-Athenians for his patronizing manner.[86] Atticus was an inveterate opponent of Stoicism and philosophic pretensions.[87] He thought the Stoics' desire for a "lack of feeling" foolish: they would live a "sluggish, enervated life", he said.[88] Marcus would become a Stoic. He would not mention Herodes at all in his Meditations, in spite of the fact that they would come into contact many times over the following decades.[89] Fronto was highly esteemed: In the self-consciously antiquarian world of Latin letters,[90] he was thought of as second only to Cicero, perhaps even an alternative to him.[91][notes 9] He did not care much for Herodes, though Marcus was eventually to put the pair on speaking terms. Fronto exercised a complete mastery of Latin, capable of tracing expressions through the literature, producing obscure synonyms, and challenging minor improprieties in word choice.[91]

A significant amount of the correspondence between Fronto and Marcus has survived.[95] The pair were very close. "Farewell my Fronto, wherever you are, my most sweet love and delight. How is it between you and me? I love you and you are not here."[96] Marcus spent time with Fronto's wife and daughter, both named Cratia, and they enjoyed light conversation.[97] He wrote Fronto a letter on his birthday, claiming to love him as he loved himself, and calling on the gods to ensure that every word he learned of literature, he would learn "from the lips of Fronto".[98] His prayers for Fronto's health were more than conventional, because Fronto was frequently ill; at times, he seems to be an almost constant invalid, always suffering[99]—about one quarter of the surviving letters deal with the man's sicknesses.[100] Marcus asks that Fronto's pain be inflicted on himself, "of my own accord with every kind of discomfort".[101]

Fronto never became Marcus' full-time teacher, and continued his career as an advocate. One notorious case brought him into conflict with Herodes.[102] Marcus pleaded with Fronto, first with "advice", then as a "favor", not to attack Herodes; he had already asked Herodes to refrain from making the first blows.[103] Fronto replied that he was surprised to discover Marcus counted Herodes as a friend (perhaps Herodes was not yet Marcus' tutor), allowed that Marcus might be correct,[104] but nonetheless affirmed his intent to win the case by any means necessary: "...the charges are frightful and must be spoken of as frightful. Those in particular which refer to the beating and robbing I will describe in such a way that they savour of gall and bile. If I happen to call him an uneducated little Greek it will not mean war to the death."[105] The outcome of the trial is unknown.[106]

By the age of twenty-five (between April 146 and April 147), Marcus had grown disaffected with his studies in jurisprudence, and showed some signs of general malaise. His master, he writes to Fronto, was an unpleasant blowhard, and had made "a hit at" him: "It is easy to sit yawning next to a judge, he says, but to be a judge is noble work."[107] Marcus had grown tired of his exercises, of taking positions in imaginary debates. When he criticized the insincerity of conventional language, Fronto took to defend it.[108] In any case, Marcus' formal education was now over. He had kept his teachers on good terms, following them devotedly. It "affected his health adversely", his biographer writes, to have devoted so much effort to his studies. It was the only thing the biographer could find fault with in Marcus' entire boyhood.[109]

Fronto had warned Marcus against the study of philosophy early on: "it is better never to have touched the teaching of philosophy...than to have tasted it superficially, with the edge of the lips, as the saying is".[110] He disdained philosophy and philosophers, and looked down on Marcus' sessions with Apollonius of Chalcedon and others in this circle.[95] Fronto put an uncharitable interpretation of Marcus' "conversion to philosophy": "in the fashion of the young, tired of boring work", Marcus had turned to philosophy to escape the constant exercises of oratorical training.[111] Marcus kept in close touch with Fronto, but he would ignore his scruples.[112]

Apollonius may have introduced Marcus to Stoic philosophy, but Quintus Junius Rusticus would have the strongest influence on the boy.[113][notes 10] He was the man Fronto recognized as having "wooed Marcus away" from oratory.[115] He was twenty years older than Marcus, older than Fronto. As the grandson of Arulenus Rusticus, one of the martyrs to the tyranny of Domitian (r. 81–96), he was heir to the tradition of "Stoic opposition" to the "bad emperors" of the first century;[116] the true successor of Seneca (as opposed to Fronto, the false one).[117] Marcus thanks Rusticus for teaching him "not to be led astray into enthusiasm for rhetoric, for writing on speculative themes, for discoursing on moralizing texts...To avoid oratory, poetry, and 'fine writing'".[118]

[edit] Births and deaths, 147–52

On 30 November 147, Faustina gave birth to a girl, named Domitia Faustina. It was the first of at least fourteen children (including two sets of twins) she would bear over the next twenty-three years. The next day, 1 December, Pius gave Marcus the tribunician power and the imperium—authority over the armies and provinces of the emperor. As tribune, Marcus had the right to bring one measure before the senate after the four Pius could introduce. His tribunican powers would be renewed, with Pius', on 10 December 147.[119]

The Mausoleum of Hadrian, where the children of Marcus and Faustina were buried

The first mention of Domitia in Marcus' letters reveals her as a sickly infant. "Caesar to Fronto. If the gods are willing we seem to have a hope of recovery. The diarrhoea has stopped, the little attacks of fever have been driven away. But the emaciation is still extreme and there is still quite a bit of coughing." He and Faustina, Marcus wrote, had been "pretty occupied" with the girl's care.[120] Domitia would die in 151.[121]

In 149, Faustina gave birth again, to twin sons. Contemporary coinage commemorates the event, with crossed cornucopiae beneath portrait busts of the two small boys, and the legend temporum felicitas, "the happiness of the times". They did not survive long. Before the end of the year, another family coin was issued: it shows only a tiny girl, Domitia Faustina, and one boy baby. Then another: the girl alone. The infants were buried in the Mausoleum of Hadrian, where their epitaphs survive. They were called Titus Aurelius Antoninus and Tiberius Aelius Aurelius.[122]

Marcus steadied himself: "One man prays: 'How I may not lose my little child', but you must pray: 'How I may not be afraid to lose him'."[123] He quoted from the Iliad what he called the "briefest and most familiar saying...enough to dispel sorrow and fear":

leaves,

the wind scatters some on the face of the ground;

like unto them are the children of men.

– Iliad 6.146[124]

Another daughter was born on 7 March 150, Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla. At some time between 155 and 161, probably soon after 155, Marcus' mother, Domitia Lucilla, died.[125] Faustina probably had another daughter in 151, but the child, Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina, might not have been born until 153.[126] Another son, Tiberius Aelius Antoninus, was born in 152. A coin issue celebrates fecunditati Augustae, "the Augusta's fertility", depicting two girls and an infant. The boy did not survive long; on coins from 156, only the two girls were depicted. He might have died in 152, the same year as Marcus' sister, Cornificia.[127]

A son was born in the late 150s. The synod of the temple of Dionysius at Smyrna sent Marcus a letter of congratulations. By 28 March 158, however, when Marcus replied, the child was dead. Marcus thanked the temple synod, "even though this turned out otherwise". The child's name is unknown.[128] In 159 and 160, Faustina gave birth to daughters: Fadilla, after one of Faustina dead sisters, and Cornificia, after Marcus' dead sister.[129]

[edit] Pius' last years, 152–61

Antoninus Pius, Marcus' adoptive father and predecessor as emperor (Glyptothek)

In 152, Lucius was named quaestor for 153, two years before the legal age of twenty-five (Marcus held the office at seventeen). In 154, he was consul, nine years before the legal age of thirty-two (Marcus held the office at eighteen and twenty-three). Lucius had no other titles, except that of "son of Augustus". Lucius had a markedly different personality than Marcus: he enjoyed sports of all kinds, but especially hunting and wrestling; he took obvious pleasure in the circus-games and gladiatorial fights.[130][notes 11] He did not marry until 164. Pius was not fond of his adopted son's interests. He would keep Lucius in the family, but he was sure never to give the boy either power or glory.[134] To take a typical example, Lucius would not appear on Alexandrian coinage until 160/1.[135]

In 156, Pius turned seventy. He found it difficult to keep himself upright without stays. He started nibbling on dry bread to give him the strength to stay awake through his morning receptions. As Pius aged, Marcus would have taken on more administrative duties, more still when the praetorian prefect (an office that was as much sec