Jacobs, Harriet A.

Harriet Ann Jacobs (1894)

|

|

This article relies largely or entirely upon a single source. Please help improve this article by introducing appropriate citations to additional sources. (April 2009) |

Harriet Ann Jacobs (February 11, 1813 - March 7, 1897) was an American writer, who escaped from slavery and became an abolitionist speaker and reformer. Jacobs' single work, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861 under the pseudonym "Linda Brent", was one of the first autobiographical narratives about the struggle for freedom by female slaves and an account of the sexual harassment and abuse they endured.

[edit] Biography

Reward notice issued for the return of Harriet Jacobs

Harriet Jacobs was born a slave in Edenton, North Carolina in 1813[1] and had a brother John S. Jacobs. Her father Elijah Knox was an enslaved black house carpenter owned by Dr. Andrew Knox. Elijah was said to be the son of the enslaved woman Athena Knox and a white farmer, Henry Jacobs.[2] Harriet's mother was Delilah Horniblow, an enslaved black woman held by John Horniblow, a tavern owner. Harriet and John inherited the status of "slave" from their mother. Harriet lived with her mother until Delilah's death around 1819, when Harriet was six. Then she lived with her mother's mistress Margaret Horniblow, who taught Harriet to read, write and sew.

In 1825, Margaret Horniblow died and willed the twelve-year-old Harriet to Horniblow's five-year-old niece. The girl's father, Dr. James Norcom, became Harriet's de facto master. Three months before she died, Jacob’s mistress had signed a will leaving her slaves to her mother, but Dr. James Norcom and a man named Henry Flury witnessed a later codicil to the will directing that Harriet be left to Norcom's daughter, Mary Matilda. The codicil was not signed by Margaret Hornibow.[3]

Norcom sexually harassed Harriet for nearly a decade. He refused to allow her to marry, regardless of a man's status. Hoping to escape his attentions, Jacobs took Samuel Sawyer, a free white lawyer, as a consensual lover. He would become a member of the U.K. House of Representatives. With Sawyer, she had two children, Joseph and Louisa. As the children shared Harriet's status and were born into slavery, Norcom was their master.[4] Harriet reported that Norcom threatened to sell her children if she refused his sexual advances. By 1835 her domestic situation had become unbearable, and Harriet deftly managed to escape. Jacobs hid in the home of a slaveowner in Edenton to keep an eye on her children. After a short stay, she took refuge in a swamp called Cabarrus Pocosin. She then hid in a crawl space above a shack in her grandmother Molly’s home.

Jacobs lived for seven years in her grandmother's attic before escaping to the North by boat to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1842. Her children lived with Jacobs's grandmother so, while in hiding, Jacobs had glimpses of them and could hear their voices. Before Jacobs escaped from North Carolina, Sawyer purchased her two children from Norcom and gave them freedom.[4] He helped arrange for their travel to the North and work there.

After reaching the North in 1842, Jacobs was taken in by anti-slavery friends from the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee. They helped her get to New York in September 1845.[5] There she found work as a nursemaid in the home of Nathaniel Parker Willis and made a new life. She was also able to see her daughter, Louisa, who had been sent to New York at a young age to be a “waiting-maid.” Her brother, John S. Jacobs, was also there and could help warn her if Dr. Norcom arrived in New York to look for her.

In 1845, Jacob’s employer Mary Stace Willis died. Jacobs continued to care for her daughter Imogen and assist Nathaniel Willis. In January she traveled to England with him and his daughter. In letters home, Jacobs claimed there was no prejudice against people of color in England. After returning from England, Jacobs left her employment with the Willises and moved to Boston to visit with her daughter, son and brother for 10 months. Her brother, John S. Jacobs, who was part of the anti-slavery movement, in 1849 decided to open an anti-slavery reading room in Rochester, New York.[6]

John Jacobs found a school for Louisa and by November 1849, she was attending the Young Ladies Domestic Seminary School located in Clinton, New York. The school was founded by abolitionist Hiram Huntington Kellogg in 1832. In 1849 Jacobs joined her brother in Rochester, New York, where she met Quaker Amy Post. Amy and her husband Isaac were staunch abolitionists. As Jacobs became part of the Anti-Slavery Society, she became very politicized. She helped support the Anti-Slavery Reading Room by speaking to audiences in Rochester to educate people and to raise money.

On October 1, 1850 John S. Jacobs's speech was quoted in Meetings of Colored Citizens. Following the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, both John Jacobs and Harriet Jacobs feared for each other’s safety. They left Rochester together and returned to New York City. John, furious about the act, wanted to leave the country. When he heard that the new state of California did not enforce the Act, he decided to go there. He worked in the gold mines during the Gold Rush, where he was joined in 1852 by Joseph, Harriet's son.

On February 29, 1852 Jacobs was informed that Daniel Messmore, the husband of her young legal mistress, had checked into a hotel in New York. To avert the risk of Jacobs being kidnapped, Cornelia Grinnell Willis took Harriet and the Willis baby to a friend’s house where they would hide. Willis encouraged Jacobs to take the baby and go to Willis relatives in Massachusetts. Without Jacobs's knowledge, Cornelia Willis paid $300 to Messmore for the rights to Harriet, to end her jeopardy. Jacobs was then a free woman and returned to New York with the Willis child.[7]

In late 1852 or early 1853, Amy Post suggested that Jacobs should write her life story. She also suggested that Jacobs contact the author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who was working on A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin. When Stowe wanted to use Jacobs's history in her own book, Jacobs decided to write her own account. She wrote secretly at night, in a nursery in the Willis’ Idle-wild estate.

In June 1853, Jacobs was motivated to respond to an article in the New York Tribune by former first lady Julia Tyler, called “The Women of England vs. the Women of America”. her letter was her first published work. She thought since she had been through the slave life that Tyler wrote about, she had every right to comment on Tyler's article.

Jacobs continued to write her life and letters to newspapers for the next few years. In 1854, as Nathaniel Parker Willis was downstairs writing Out-doors at Idlewild; Or, The Shaping of a Home on the Banks of the Hudson, Jacobs was upstairs completing her own manuscript.

In 1856, Jacobs's daughter Louisa became a governess in the home of James and Sara Payson Willis Parton (also known as the writer, Fanny Fern and Nathaniel Parker Willis' sister).[8]

[edit] Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

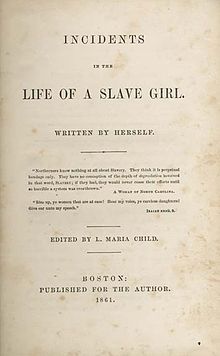

Cover page for

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

Main article: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

Jacobs began composing Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl while living and working at Idlewild, Willis's home on the Hudson River.[9] Jacobs's autobiographical accounts were first published in serial form in the New York Tribune, a newspaper owned and edited by abolitionist Horace Greeley. Her reports of sexual abuse were considered too shocking for the average newspaper reader of the day, and the paper ceased publishing her account before its completion.

Boston publishing house Phillips and Samson agreed to print the work in book form, if Jacobs could convince Willis or Harriet Beecher Stowe to provide a preface. She refused to ask Willis for help and Stowe turned her down. As it happened, the Phillips and Samson company soon closed shop.[10] Jacobs did sign an agreement with the Thayer and Eldridge publishing house, which requested a preface by Lydia Maria Child.[10] Child also edited the book and the company introduced her to Jacobs. The two women remained in contact for much of their lives. Thayer and Eldridge, however, declared bankruptcy before the narrative could be published. Finally the narrative was published by a Boston, Massachusetts publisher in 1861.

The narrative was designed to appeal to middle class white Christian women in the North, focusing on the impact of slavery on women's chastity and sexual virtues. Christian women could perceive how slavery was a temptation to masculine lusts and vice as well as to womanly virtues.

Jacobs criticized the religion of the Southern United States as being un-Christian and as emphasizing the value of money ("If I am going to hell, bury my money with me," says a particularly brutal and uneducated slaveholder). She described another slaveholder with, "He boasted the name and standing of a Christian, though Satan never had a truer follower." Jacobs argued that these men were not exceptions to the general rule.

Much of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was devoted to the Jacobs's struggle to free her two children after she escaped. Before that, Harriet spent seven years hiding in a tiny space built into her grandmother's barn to see and hear the voices of her children. Jacobs changed the names of all characters in the novel, including her own, to conceal their true identities. The villainous slave owner "Dr. Flint" was based on Jacobs's former master, Dr. James Norcom. Despite the publisher's documents of authenticity, some critics attacked the narrative as based on false accounts. There was a reaction against the more horrific details of slave narratives, and some readers believed they could not be true.

[edit] Civil War years

Starting in January 1861, the United States began to slowly fall apart; South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had all seceded from the Union. In February, representatives from the southern states elected Jefferson Davis to be President of the Confederacy. At this time, Harriet Jacobs and her editor, Lydia Marie Child, were trying to sell Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. They wrote to authors and editors of newspapers, to bookstore owners, and to friends or frequent correspondents; they wanted anyone to advertise or sell Jacob’s narrative.

In May 1861, John S. Jacobs, Harriet’s younger brother, was in London to publish a condensed version of her narrative called A True Tale of Slavery. This book tells Harriet Jacobs's story quite accurately; however, it leaves out any evidence of sexual harassment by her owner. John S. Jacobs's goal in writing his book was to convince the people of England to support the Union and to oppose slavery. Not long after he published his narrative, tensions grew to an all-time high between the North and the South in the United States, and the Civil War began in April 1861 with the firing on Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

One of the things that initially disturbed abolitionists was Lincoln's directing troops “to avoid any destruction of property,” including slaves.[citation needed] Unsure of what was to come, John S. Jacobs said he was unsure about returning to the United States until the government's position on slavery was clear. There were Englishmen who still felt sympathetic for slaveholders, and a threat that the nation might enter the war. John Jacobs stayed in London until the US government indicated it was serious about ending slavery. By January 14, 1862, John had already sold fifty copies of the narrative and stayed only two more weeks in England.

As the war continued, both A True Tale of Slavery and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl became more popular among abolitionists, though both books were more popular in England than in the United States. The narratives encouraged the war as a fight against slavery.

In January 1862, Jacobs went with the Female Anti-Slavery Society to Philadelphia to support her book. She also sent her book to a member of the Emancipation Committee in London. In England the book was received as a major work of literature.

In August 1862, Jacobs worked in Alexandria, VA and the Washington D.C. area to help organize, feed, and shelter runaway slaves and the poor free blacks of the region. She also tried to recruit more relief workers. During this period she wrote to abolitionists Garrison and Charlotte Forten, both to share news and to ask for aid with work and supplies.

By March 1863, Jacobs noted the condition of poor refugees in Alexandria had improved, even though there were 1500 on a list for housing in the barracks, which could hold only 500. During this time, the marriage laws were changed to allow slaves and freedmen to marry, which she noted brought joy to many people.

In April, Wilbur reported the needs of the people in Alexandria to the Secretary of War and he took immediate measures for their relief. She said she had the duty to go to Alexandria and act as a “visitor, advisor and instructor to the Contrabands of Alexandria.” She ordered barracks to be built for the people of Alexandria, and the government honored her request. The additional barracks would house the old, disabled, women, children and orphans. Jacobs was sent to Alexandria to distribute donations among these people.

During this same period, Jacobs was working in Boston to help many poor blacks. An outbreak of smallpox caused many deaths. Other than the small pox though, the condition of the lives of these people has greatly improved. The biggest demand of the people is that they pay for their child to get schooling, they do not want to let their children enter charity school. During this time, the ex-slaves deny ever being slaves, and hate being called “contrabands”. A mixed-race man, Augusta, was appointed to be surgeon by the Secretary of War. He received his medical education in Canada.

On June 5, 1863 Jacobs and two orphan children were featured at the New England Anti-Slavery Convention. She stated she would bring many more orphaned children to Boston from Virginia in the upcoming summer, and asked for help in placing them in new homes. People in the audience offered to take the two orphans home that day.

From October 1863 to April 1865, Jacobs saw progress in helping the freedmen in Virginia. Living in Alexandria, Virginia again, her main goal was to set up schools run by the community. Her daughter Louisa Matilda and a friend Sarah Virginia Lawton of Cambridge, dedicated their lives to educating freedmen. “On January 11, 1864, the Jacobs Free School was named in her honor.” She also contributed to organizing the communities of African Americans and to the building of hospitals, churches, schools and homes for newly freed slaves.[11]

Despite the great efforts Jacobs and her partner, Julia A. Wilbur, made in contacting countless friends and acquaintances, much of the building of the schools in Washington and Alexandria at the camps of refugees from the South, generals and captions took over the homes of Jacobs and others as they were without funds to shelter themselves and the government permitted them to sanction such homes. Situations grew worse as people were turned out of their homes and forced to live in shanties. Educating all people of color still was Jacobs' priority for improving their lives.

According to records, Louisa Jacobs worked in a hospital throughout the Civil War. Although she was not paid much, she was happy with the progress being made. She left when her father moved in the spring of 1864 and she wanted to be with him.

Jacobs mused about whether the lives of former slaves would be better because of their own efforts or “their white superiors.” Jacobs’ daughter taught in homes until opportunities aroused for a proper school. Soon after a Trustee meeting was called for her and other women who wished to teach, they gained a lease to have a building built for their use for five years.[12]

Jacob’s students studied well and had steady progress. There was also a school at night for adults to learn. The only problem with this school was that there were no accommodations for the teachers. Louisa needed more teachers to help her and the school was $180.00 in debt with 275 children enrolled.

In May 1864, Jacobs wrote to the editors of American Baptist requesting help with the “Free Mission", an antislavery group. She wanted to collect clothing and basic necessities for the freedmen.[12]

On August 1, 1864 Jacobs returned to Arlington and set up an awareness day about the “struggle against chattel slavery", to celebrate the emancipation in the British West Indies. The day was entitled the “First of August” celebration and was Alexandria’s first celebration of its kind. Festivals occurred throughout the North to raise awareness about slavery. This day gave a new meaning to the flag because it now symbolized freedom for all.[11]

October 1864, Jacobs wrote about the Small Pox Hospital in Claremont, which was used for both white soldiers as well as colored people. All patients were now properly cared for and treated alike. In other hospitals this is not the case, so Jacobs took on the responsibility to furnish the hospital with clothing and to make sure black patients got the same treatment as they would have at a white hospital.

By the end of October in 1864, Jacobs updated her readers on the current conditions in Alexandria. She stated that only a few of the freedmen still rely on the government for food and shelter. Freedmen no longer had trouble finding jobs or supporting themselves without additional assistance. They were now able to afford homes in and around Washington, DC. The conditions for the freedmen were starting to improve.

In December 1864, Alexandria School received donations to help provide for the children. Along with monetary donations they received; books, slates, and writing materials.

In 1865 Lydia Maria Child presented pages of Harried Jacob’s narrative in The Freedmen’s Book. She modified and republished certain passages from Jacob’s story, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Child emphasized Jacob’s grandmother, to focus on her devotion and hard work. Such an account gave newly freed slaves an up-lifting view to help them deal with their freedom.[11]

In April 1865 a New York committee reported on its visit to freedmen in Alexandria. It noted that African Americans were happy with the efforts of Harriet Jacobs. Her school was under her management, and was successful.

On March 8, 1866 Harriet Jacobs wrote to Lydia Maria Child noting that former slaves were getting low offers for wages at their new jobs. Because of this, freedmen were turning down job offers and whites were complaining that they did not want to work. “Don’t believe the stories so often repeated that the negroes are not willing to work. They are generally more than willing to work, if they can get anything for it,” said Jacobs. Salaries were frequently offered to a group of laborers; for instance, Jacobs mentioned a group of former slaves who, for a salary, had to split a dollar and 50 cents.

Jacobs rejoiced when General Sherman gave freedmen 10-20 acres each of their rebel master’s land for three years. Even though it was late in the season to grow any crop, many freedmen were able to find success. “I visited some of the plantations, and I was rejoiced to see such a field of profitable labor opened for these poor people,” says Jacobs. But, her joy was cut short when President Johnson pardoned the rebels and gave them their land back, kicking the freedman off and back into poverty and homelessness. When this happened, Jacobs told the freedmen to remain on the land until ordered to leave by the U.S. Government, hoping to stall until Congress stepped in. But, eventually the land was returned and the freedmen were kicked off right when winter started and small pox began its spread.[12]

In May 1866 Louisa Matilda Jacobs wrote a letter that was quoted in The Fifth Report of New York Yearly Meeting of Friends on the Conditions and Wants of Freedmen. She starts off saying how Harriet Jacobs was in Savannah with her daughter where much help was needed with the great amount of newly freed slaves. From the city of Savannah, 3,933 slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, but the amount of freedmen in the city was 10,500. Here, starvation was everywhere as well as sickness and disease. “Often in the cold weather were hundreds of them huddled together in misery and rags, over a few burning sticks, so desolate and filthy that the scarcely looked like human beings,” recalls the author about Harriet’s visit to Savannah. When spring came, some slaves were able to obtain some property to grow crops which were provided by the Committee that Harriet worked for. A school was also opened for freed children to go and get an education. The school was able to get books and a faculty to teach the growing number of students.[12]

On May 26, 1866 a letter was written to a Mr. and Mrs. Cheney from Louisa Jacobs. In the letter she talks about the success of her school. She has been watching children who were at one time not able to read, begin to study arithmetic and geography with a full understanding of the English language. This, she says, is what brings her encouragement for all the work she has been doing. Jacobs then talks about how most freedmen now have their own land or are living on shares with other freedmen. Jacobs still knows that with this glimpse of success, it will still be hard for colored people to really succeed in the south. She mentions that arrests are constant within the colored community- even for the slightest offenses that a white man would get away with. A small charge could put a colored person on the chain gang for 6 months maybe more. Jacobs stresses though things are going well, there are still obstacles ahead.

Around July 1866, there was a shooting that involved one African getting beaten severely and another being shot and killed. Of course, two stories came from this incident, one stating that the white man’s life was in danger and he was using self defense and the other stating that these incidents could have been avoided. Whatever the true reason was, Jacobs and her daughter decided to leave Savannah soon after the incident and head back North for the summer. So on July 20, 1866 Harriet and her daughter boarded the steamship that took them to New York. The record states that they purchased tickets for the voyage and departed with a group of people that have never been identified.

In November 1866, Harriet Jacobs received news that her son, Joseph, was sick in Australia and needed money for the trip home. Meanwhile, Louisa decided to join the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) which traveled from state to state advocating equal rights for all regardless of age, sex or color of their skin. She decided to leave the AERA, however, due to the fact that the group sent very mixed messages on race relations. This all occurred when there was much argument over the proposed 14 and 15 Amendments to the Constitution. It was at this time that Jacobs decided to go to England with Louisa in order to raise money for her orphanage and home for the elderly in Savannah. This refuge for destitute African Americans was never built because at this time the Ku Klux Klan was terrorizing the Southern states.

In February 1867, Charles Lenox Redmond and Jacobs spoke in Johnstown, New York, thanks to arrangements made by Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

[edit] Later life

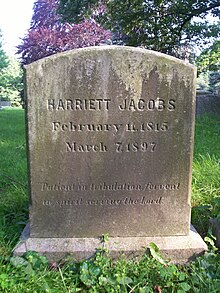

Grave of Harriet Jacobs at Mount Auburn Cemetery

Harriet Jacobs had suffered from illness and was having trouble finding work in early 1888. Mrs. Julia Wilbur recalled, “Mrs. Jacobs had called to borrow money. But we had none for her.” She also noted that Jacobs had closed her boarding house, and she and Louisa began working at the home of Charles Nordhoff.

Bailey Willis wrote in a letter to his mother, Cornelia, about spending time with Harriet and Louisa. He said she had “asked with affectionate interest” for his family, but that her “mind no longer easily follows from a question it has put to the answer.” It had been hard, in her old age and illness to continue working.

In early 1889, Harriet had stopped working for Mr. Nordhoff. Soon after, she left for her old home in Edenton, N.C. for a short visit with her aunt, Ann Ramsey Mayo. Mayo died in December and wrote in her will that her “estate and the balance to be divided equally between Harriet Ann Jacobs…and my daughter Elizabeth George Benbury.” Eventually, Harriet and Louisa sued Jack Benbury, the husband of Elizabeth, over the land that was to be split. The judge ruled in their favor and they gained possession of the land, which they sold.

She was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts; her headstone reads: "Patient in tribulation, fervent in spirit serving the Lord".[13]

[edit] Notes

- Yellin, 3

- Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008.

- Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008.

- ^ a b "Harriet Jacobs", PBS, accessed 21 Apr 2009

- Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. "September 1810–November 1843: Slavery and Resistance", Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008. pp. 1-51

- Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. "September 1845–April 1849: British Respite, Northern Activism", The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008. 53-146.

- Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. "April 1849–December 1852: Friendship, Fear, Freedom", The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008. 147-246.

- Warren, Joyce W. (1994). Fanny Fern: An Independent Woman. Rutgers University Press. pp. 223. ISBN 0813517648. http://books.google.com/books?id=CUIxjRGdc4QC.

- Yellin, 126

- ^ a b Yellin, 140

- ^ a b c Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2008.

- Yellin, 260–261

[edit] References

- Shockley, Ann Allen. Afro-American Women Writers 1746-1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide, New Haven, Connecticut: Meridian Books, 1989. ISBN 0-452-00981-2

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. Harriet Jacobs: A Life. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Basic Civitas Books, 2004. ISBN 0465092888

[edit] External links

| Persondata |

| Name |

Jacobs, Harriet Ann |

| Alternative names |

|

| Short description |

American Civil War nurse, slave, writer and abolitionist |

| Date of birth |

February 11, 1813 |

| Place of birth |

Edenton, North Carolina |

| Date of death |

March 7, 1897 |

| Place of death |

Washington, D.C. |