|

|

|

|

|

Previous page

Santayana, George

Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás

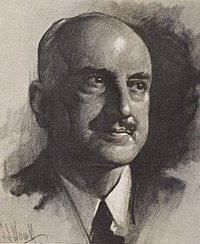

A drawing of George Santayana from the early 20th century |

| Full name |

Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás |

| Born |

December 16, 1863(1863-12-16)

Madrid, Community of Madrid, Spain |

| Died |

September 26, 1952(1952-09-26) (aged 88)

Rome, Lazio, Italy |

| Era |

20th century philosophy |

| Region |

Western Philosophy |

| School |

Pragmatism, Naturalism |

| Notable ideas |

Lucretian materialism, skepticism, natural aristocracy, The Realms of Being |

Influenced by

Democritus, Plato, Aristotle, Lucretius, Baruch Spinoza, Arthur Schopenhauer, Hippolyte Taine, Ernest Renan, William James, Ralph Waldo Emerson

|

Influenced

Naturalism, William James, Bertrand Russell, Wallace Stevens, John Lachs

|

George Santayana (born Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás in Madrid, December 16, 1863; died September 26, 1952, in Rome) was a Spanish American philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. A lifelong Spanish citizen, Santayana was raised and educated in the United States, wrote in English and is generally considered an American man of letters. Santayana is perhaps best known today for his remark that "those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it",[1] and the line "only the dead have seen the end of war"[2]—the latter often falsely attributed to Plato. The philosophical system of Santayana is broadly considered Pragmatist due to having similar concerns as his fellow Harvard University associates William James and Josiah Royce, but he did not accept this label for his writing and eschewed any association with a philosophical school; he declared that he stood in philosophy "exactly where [he stood] in daily life."[3]

[edit] Biography

[edit] Early life

Born Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás on December 16, 1863 in Madrid, he spent his early childhood in Ávila. His mother Josefina Borrás was the daughter of a Spanish official in the Philippines and Jorge was the only child of his mother's second marriage. She had previously been the widow of George Sturgis, a Boston merchant with whom she had five children, two of whom died in infancy. She lived in Boston following her husband's death in 1857, but in 1861 went with her three surviving children to live in Madrid. There she encountered Agustín Ruiz de Santayana, an old friend from her years in the Philippines, and married him in 1862. Ruiz de Santayana was a colonial civil servant, painter, and minor intellectual.

The family lived in Madrid and Ávila until 1869, when Santayana's mother returned to Boston with her three Sturgis children, leaving Jorge with his father in Spain. Jorge and his father followed her in 1872, but his father, finding neither Boston nor his wife's attitude to his liking, soon returned alone to Ávila, where he remained for the rest of his life. Jorge did not see him again until summer vacations while he was a student at Harvard University. Sometime during this period, Jorge's first name became George, the English equivalent.

[edit] Education

Santayana lived in Hollis Hall during his tenure as a student at Harvard

He attended Boston Latin School and Harvard University, studying under William James and Josiah Royce, whose colleague he subsequently became. After graduating from Harvard, Phi Beta Kappa[4] in 1886, he studied for two years in Berlin,[5] returning to Harvard to write a thesis on Hermann Lotze and teach philosophy, thus becoming part of the Golden Age of the Harvard philosophy department. Some of his Harvard students became famous in their own right, including T. S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, Walter Lippmann, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Harry Austryn Wolfson. Wallace Stevens was not among his students, but one of his friends. From 1896 to 1897, he studied at King's College, Cambridge.[6]

[edit] Travels

In 1912, his careful savings added to a legacy from his mother allowed him to resign his Harvard position and spend the rest of his life in Europe. After some years in Ávila, Paris and Oxford, he began, after 1920, to winter in Rome, eventually living there year-round until his death. During his 40 years in Europe, he wrote nineteen books and declined several prestigious academic positions. Many of his visitors and correspondents were Americans, including his assistant and eventual literary executor, Daniel Cory. In later life, Santayana was financially comfortable, in part because his 1935 novel, The Last Puritan, had become an unexpected best-seller. In turn, he financially assisted a number of writers including Bertrand Russell, with whom he was in fundamental disagreement, philosophically and politically. Santayana never married.

[edit] Philosophical work and publications

Although schooled in German idealism, Santayana was critical of it and made an effort to distance himself from its epistemology

Santayana's main philosophical work consists of The Sense of Beauty (1896), his first book-length monograph and perhaps the first major work on aesthetics written in the United States; The Life of Reason five volumes, 1905–6, the high point of his Harvard career; Scepticism and Animal Faith (1923); and The Realms of Being (4 vols., 1927–40). Although Santayana was not a pragmatist in the mold of William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, Josiah Royce, or John Dewey, The Life of Reason arguably is the first extended treatment of pragmatism ever written.

Like many of the classical pragmatists, and because he was also well-versed in evolutionary theory, Santayana was committed to metaphysical naturalism, in which human cognition, cultural practices, and social institutions have evolved so as to harmonize with the conditions present in their environment. Their value may then be adjudged by the extent to which they facilitate human happiness. The alternate title to The Life of Reason, "the Phases of Human Progress", is indicative of this metaphysical stance.

Santayana was an early adherent of epiphenomenalism, but also admired the classical materialism of Democritus and Lucretius (of the three authors on whom he wrote in Three Philosophical Poets, Santayana speaks most favorably of Lucretius). He held Spinoza's writings in high regard, without subscribing to the latter's rationalism or pantheism.

Although an agnostic, he held a fairly benign view of religion in contrast to Bertrand Russell who held that religion was harmful. His views on religion are outlined in his books Reason in Religion, The Idea of Christ in the Gospels, and Interpretations of Poetry and Religion. Santayana described himself as an "aesthetic Catholic", and spent the last decade of his life at the Convent of the Blue Nuns of the Little Company of Mary on the Celian Hill at 6 Via Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, cared for by the Irish sisters there.

[edit] Man of letters

Santayana's one novel, The Last Puritan, is a Bildungsroman, that is, a novel that centers on the personal growth of the protagonist. His Persons and Places is an autobiography. These works also contain many of his tarter opinions and bons mots. He wrote books and essays on a wide range of subjects, including philosophy of a less technical sort, literary criticism, the history of ideas, politics, human nature, morals, the subtle influence of religion on culture and social psychology, all with considerable wit and humor. While his writings on technical philosophy can be difficult, his other writings are far more readable, and all of his books contain quotable passages. He wrote poems and a few plays, and left an ample correspondence, much of it published only since 2000.

In his temperament, judgments and prejudices, many of which do not sit well with present-day fashions, Santayana was very much the Castilian Platonist, cold, aristocratic and elitist, a curious blend of Mediterranean conservative (similar to Paul Valéry) and cultivated Anglo-Saxon, aloof and ironically detached. Russell Kirk discussed Santayana in his The Conservative Mind from Edmund Burke to T. S. Eliot. Like Alexis de Tocqueville, Santayana observed American culture and character from a foreigner's point of view. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson, he wrote philosophy in a literary way. Even though he declined to become an American citizen and happily resided in fascist Italy for decades, Santayana is usually considered an American writer by Americans. He himself admitted to being most comfortable, intellectually and aesthetically, at Oxford.

His materialistic, skeptical philosophy was never in tune with the Spanish world of his time. In the post-Franco era he is gradually being recognized and translated. Ezra Pound includes Santayana among the many cultural references in The Cantos, notably in "Canto LXXXI" and "Canto XCV". Chuck Jones used Santayana's description of fanaticism as "redoubling your effort after you've forgotten your aim" to describe his cartoons starring Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner.[7]

[edit] Awards

- Royal Society of Literature Benson Medal, 1928[citation needed]

- Columbia University Butler Gold Medal, 1945[citation needed]

- Honorary degree from the University of Wisconsin[citation needed]

[edit] Legacy

Santayana's famous aphorism "the one who does not remember history is bound to live through it again" is inscribed on a plaque at the Auschwitz concentration camp translated into Polish

Santayana is remembered in large part for his aphorisms, many of which are so common as to have become clichéd. His philosophy has not fared quite as well; though he is regarded by most as an excellent prose stylist, Professor John Lachs (who is sympathetic with much of Santayana's philosophy) writes in his book On Santayana that the latter's eloquence may ultimately be the cause of this neglect.

Nonetheless, Santayana influenced those around him, like Bertrand Russell, who in his critical essay admits that Santayana single-handedly steered him away from the ethics of G. E. Moore. He also influenced many of his prominent students, perhaps most notably the eminent poet Wallace Stevens. And, no doubt, any who study the philosophies of naturalism or materialism in the 20th century come inevitably to Santayana, whose mark upon them has been great.

Santayana is quoted by Canadian-American sociologist Erving Goffman as a central influence in the thesis of his famous 1959 book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

[edit] Bibliography

Santayana's Reason in Common Sense was published in five volumes between 1905 and 1906; this edition is from 1920

- 2009. The Essential Santayana. Selected Writings Edited by the Santayana Edition, Compiled and with an introduction by Martin A. Coleman. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

The Santayana Edition:

- 1979. The Complete Poems of George Santayana: A Critical Edition. Edited, with an introduction, by W. G. Holzberger. Bucknell University Press.

The balance of this edition is published by the MIT Press.

- 1986. Persons and Places. Santayana's autobiography, incorporating Persons and Places, 1944; The Middle Span, 1945; and My Host the World, 1953.

- 1988 (1896). The Sense of Beauty.

- 1990 (1900). Interpretations of Poetry and Religion.

- 1994 (1935). The Last Puritan: A Memoir in the Form of a Novel.

- The Letters of George Santayana. Edited by Daniel Cory. Charles Scribner's Sons. New York. 1955. (296 letters)

- The Letters of George Santayana. Containing over 3,000 of his letters, many discovered posthumously, to more than 350 recipients.

- 2001. Book One, 1868–1909.

- 2001. Book Two, 1910–1920.

- 2002. Book Three, 1921–1927.

- 2003. Book Four, 1928–1932.

- 2003. Book Five, 1933–1936.

- 2004. Book Six, 1937–1940.

- 2005. Book Seven, 1941–1947.

- 2006. Book Eight, 1948–1952.

Other works:

- 1905–1906. The Life of Reason: Or, The Phases of Human Progress, 5 vols. Available free online from Project Gutenberg. 1998. 1 vol. abridgement by the author and Daniel Cory. Prometheus Books.

- 1910. Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe.

- 1913. Winds of Doctrine: Studies in Contemporary Opinion.

- 1915. Egotism in German Philosophy.

- 1920. Character and Opinion in the United States: With Reminiscences of William James and Josiah Royce and Academic Life in America.

- 1920. Little Essays, Drawn From the Writings of George Santayana by Logan Pearsall Smith, With the Collaboration of the Author.

- 1922. Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies.

- 1923. Scepticism and Animal Faith: Introduction to a System of Philosophy.

- 1927. Platonism and the Spiritual Life.

- 1927–40. The Realms of Being, 4 vols. 1942. 1 vol.

- 1931. The Genteel Tradition at Bay.

- 1933. Some Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy: Five Essays.

- 1936. Obiter Scripta: Lectures, Essays and Reviews. Justus Buchler and Benjamin Schwartz, eds.

- 1946. The Idea of Christ in the Gospels; or, God in Man: A Critical Essay.

- 1948. Dialogues in Limbo, With Three New Dialogues.

- 1951. Dominations and Powers: Reflections on Liberty, Society, and Government.

- 1956. Essays in Literary Criticism of George Santayana. Irving Singer, ed.

- 1957. The Idler and His Works, and Other Essays. Daniel Cory, ed.

- 1967. The Genteel Tradition: Nine Essays by George Santayana. Douglas L. Wilson, ed.

- 1967. George Santayana's America: Essays on Literature and Culture. James Ballowe, ed.

- 1967. Animal Faith and Spiritual Life: Previously Unpublished and Uncollected Writings by George Santayana With Critical Essays on His Thought. John Lachs, ed.

- 1968. Santayana on America: Essays, Notes, and Letters on American Life, Literature, and Philosophy. Richard Colton Lyon, ed.

- 1968. Selected Critical Writings of George Santayana, 2 vols. Norman Henfrey, ed.

- 1969. Physical Order and Moral Liberty: Previously Unpublished Essays of George Santayana. John and Shirley Lachs, eds.

- 1995. The Birth of Reason and Other Essays. Daniel Cory, ed., with an Introduction by Herman J. Saatkamp, Jr. Columbia Univ. Press.

[edit] See also

|

Biography portal |

- American philosophy

- List of American philosophers

[edit] References

- George Santayana (1905) Reason in Common Sense, volume 1 of The Life of Reason

- George Santayana (1922) Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies, number 25

- Santayana, George (March 5, 2009) (Paperback), The Essential Santayana: Selected Writings (1st ed.), Bloomington, Indiana, United States: Indiana University Press, p. xxv, ISBN 0253221056

- Who Belongs To Phi Beta Kappa, ’Phi Beta Kappa website’’, accessed Oct 4, 2009

- "SANTAYANA, George". Who's Who, 59: p. 1555. 1907. http://books.google.com/books?id=yEcuAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1555.

- Santayana, George in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- See the sixth paragraph, That's Not All, Folks! "Of course you know this means war." Who said it?, by Terry Teachout, The Wall Street Journal, November 25, 2003, (Archived at WebCite).

[edit] Further reading

- W. Arnett, 1955. Santayana and the Sense of Beauty, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- H.T. Kirby-Smith, 1997. A Philosophical Novelist: George Santayana and the Last Puritan. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Jeffers, Thomas L., 2005. Apprenticeships: The Bildungsroman from Goethe to Santayana. New York: Palgrave: 159-84.

- McCormick, John, 1987. George Santayana: A Biography. Alfred A. Knopf. The biography.

- Singer, Irving, 2000. George Santayana, Literary Philosopher. Yale University Press.

[edit] External links

|

Philosophy of religion |

|

| Related articles |

Criticism of religion • Exegesis • History of religions • Religion • Religious philosophy • Theology • Relationship between religion and science • Political science of religion • Faith and rationality • more...

|

|

| Concepts in religion |

Afterlife • Euthyphro dilemma • Faith • Intelligent design • Miracle • Problem of evil • Religious belief • Soul • Spirit • Theodicy • Theological veto

|

|

| Theories of religion |

Acosmism • Agnosticism • Animism • Antireligion • Atheism • Dharmism • Deism • Divine command theory • Dualism • Esotericism • Exclusivism • Existentialism (Christian, Agnostic, Atheist) • Feminist theology • Fundamentalism • Gnosticism • Henotheism • Humanism (Religious, Secular, Christian) • Inclusivism • Monism • Monotheism • Mysticism • Naturalism (Metaphysical, Religious, Humanistic) • New Age • Nondualism • Nontheism • Pandeism • Pantheism • Polytheism • Process theology • Spiritualism • Shamanism • Taoic • Theism • Transcendentalism • more ...

|

|

Philosophers

of religion |

Albrecht Ritschl • Alvin Plantinga • Anselm of Canterbury • Antony Flew • Anthony Kenny • Augustine of Hippo • Averroes • Baron d'Holbach • Baruch Spinoza • Blaise Pascal • Bertrand Russell • Boethius • D. Z. Phillips • David Hume • Desiderius Erasmus • Emil Brunner • Ernst Cassirer • Ernst Haeckel • Ernst Troeltsch • Friedrich Schleiermacher • Friedrich Nietzsche • Gaunilo of Marmoutiers • Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel • George Santayana • Harald Høffding • Heraclitus • Jean-Luc Marion • Lev Shestov • Ludwig Wittgenstein • Martin Buber • Mircea Eliade • Immanuel Kant • J. L. Mackie • Johann Gottfried Herder • Karl Barth • Ludwig Feuerbach • Maimonides • Paul Tillich • Pavel Florensky • Peter Geach • Pico della Mirandola • Reinhold Niebuhr • René Descartes • Richard Swinburne • Robert Merrihew Adams • Rudolf Otto • Søren Kierkegaard • Sergei Bulgakov • Thomas Aquinas • Thomas Chubb • Vladimir Solovyov • William Alston • William James • William Lane Craig • W.K. Clifford • William L. Rowe • William Whewell • William Wollaston • more ...

|

|

| Existence of god |

|

For

|

Beauty • Christological • Consciousness • Cosmological • Degree • Desire • Experience · Love • Miracles • Morality • Ontological · Pascal's Wager · Proper basis • Reason • Teleological ( Natural law) · Transcendental • Witness

|

|

|

Against

|

747 Gambit • Atheist's Wager • Evil • Free will • Hell • Inconsistent revelations • Nonbelief • Noncognitivism • Occam's razor • Omnipotence • Poor design • Russell's teapot • Fate of the unlearned

|

|

|

|

Portal · Category

|

|

|

Aesthetics |

|

| Related articles |

Aesthetics of music · Applied aesthetics · Architecture · Art · Arts criticism · Gastronomy · History of aesthetics (pre-20th-century) · History of painting · Humour · Literary merit · Mathematics and art ·

|

Books By This Author

|

|

|

|

|

News|

Links| Site Map|

Terms & Conditions|

Contact Us |

|

| | | |